Lichens are able to colonize places where there are extremes of humidity, temperature and light, and they often occur in places where few other macroscopic living things can survive.

Lichens absorb water from the atmosphere, but unlike plants they have no means of keeping water within the lichen during dry spells. Water content can fall to 15-30% and the lichen is then metabolically inactive. As soon as humidity rises, the thallus absorbs water, the cortex becomes translucent, and if there is sufficient light the algae begin photosynthesis within minutes.

Photosynthesis generates carbohydrates, and these are absorbed by the fungus as sugar alcohols or glucose. The fungus rapidly converts them to mannitol for storage, making them inaccessible to the photobionts. Lichens containing cyanobacteria also benefit from their ability to fix inorganic nitrogen from the air, a nutrient that is often limiting but crucial for protein synthesis.

Lichens are slow growing and can get the nutrients they need from rain water and dust. Bird droppings provide high levels of nitrogen.

Reproductive strategies

Lichen associations can reproduce in two main ways:

- sexual reproduction and spore production by the fungi, followed by re-association with a photobiont

- vegetative, or clonal, reproduction, when both partners disperse together, maintaining a symbiotic relationship across generations.

Sexual reproduction produces genetic variability, important in enabling organisms to adapt to change, but in lichens spores are only produced by the fungal partner. Soon after germination they must quickly form an association with a suitable alga if they are to develop into a young lichen. The chances of this for an individual spore are low, so lichens have developed various strategies to make it more likely:

- some produce a large number of very small and short-lived spores.

- others produce fewer but larger spores with a thick wall, which can remain viable for a longer period during which they may come in contact with a suitable alga.

- others produce spores with many nuclei, each of which is capable of germination.

If a spore is successful in finding the right species of algae, either free-living or within another lichen, it will envelop it with hyphae and start to form a new thallus. In the early stages, some lichens may develop by associating with an alga that is not the preferred one for that species. It may not be able to survive long in this association but for the fungus this extends the period during which the correct alga may be contacted.

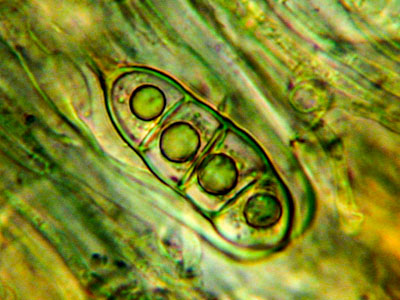

%20red.jpg) Most lichenised fungi are ascomycetes, and these produce their spores in sac-like asci held vertically in a “fruiting body”. These fruiting bodes may be disc-shaped (apothecia) with a margin of the same or a different colour, stalked, flask-shaped (perithecia) or elongate (lirellae). The structure of these and of the asci and spores themselves is the basis of most lichen classification. The “fruiting bodies” are often long-lived and continue to produce spores for many years, while others are seen briefly when conditions are cool, and moist.

Most lichenised fungi are ascomycetes, and these produce their spores in sac-like asci held vertically in a “fruiting body”. These fruiting bodes may be disc-shaped (apothecia) with a margin of the same or a different colour, stalked, flask-shaped (perithecia) or elongate (lirellae). The structure of these and of the asci and spores themselves is the basis of most lichen classification. The “fruiting bodies” are often long-lived and continue to produce spores for many years, while others are seen briefly when conditions are cool, and moist.

Vegetative dispersal is important in many species, and some have never been found with sexual fruiting bodies. Vegetative propagules contain both algal cells and fungal hyphae. Some are just broken fragments of thallus. Soredia are small powdery propagules containing a few algal cells and fungal hyphae, sometimes produced in structures called soralia. Isidia are detachable growths on the thallus surrounded by a protective cortex. These propagules may be dispersed by the wind, rain, insects, birds or even humans. The few that land in a suitable place may succeed in developing into a new lichen, but again the chances for survival of an individual propagule is low.

Lichen substances

Lichens produce secondary substances known as lichen compounds. They may be present in very high concentrations, up to 20% of the dry weight of the lichen. Many are waste products, but some also have other benefits to the lichen:

- a bitter taste may make the lichen unpalatable to grazing slugs and snails

- protection against ultraviolet radiation, such as the orange pigment in Xanthoria parietina and the reflective calcium oxalate crystals that form a pruina over the apothecia of Physcia aipolea.

- antibiotic properties

- locking up heavy metals in a form which makes them less toxic

- helping to dissolve normally insoluble minerals essential to growth

- hydrophobic (unwettable) lichen substances improve gas exchange in the medulla in wet conditions.

These lichen substances are detectable by chemical spot tests and thin layer chromatography.